The interpretation of the Christian appropriation of Alexandria’s urban topography as the victory of Christianity in the entire Empire was echoed in the triumphalist rhetoric of Nicene ecclesiastical historians. Additionally, it served for a long time to modern historiography as a paradigmatic example of a trend that was assumed to have emerged in the Empire. This perspective, however, has three serious shortcomings of a theoretical-methodological nature which this Ph.D. project is seeking to overcome.

Research

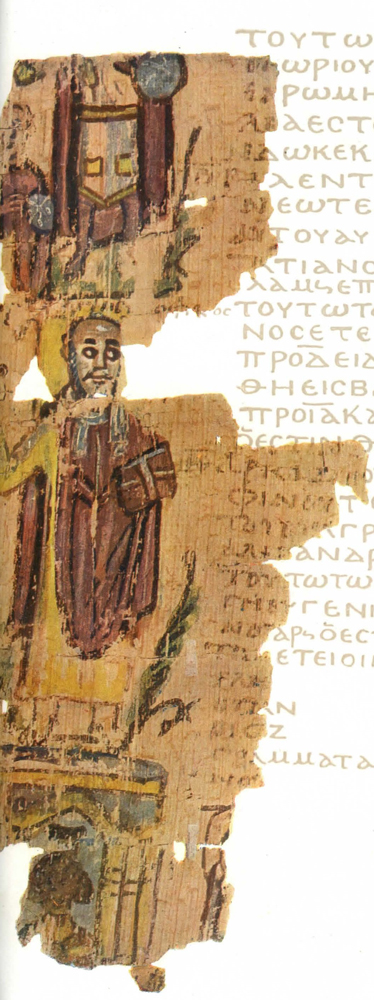

Bishop Theophilus standing atop bust of Serapis (Serapeum?), from a fifth-century Alexandrian world chronicle | Source: Bauer/Strzygowski, Eine Alexandrinische Weltchronik (Vienna, 1905), fig. VI verso.

Alexandria, the second-biggest city of the Roman Empire, has always been of peculiar interest for scholars in the field of ancient history. Owing to the relative lack of archaeological evidence, however, one had to rely on literary sources, which facilitated the emblematic reduction of the metropolis as holistic entity according to the particular period of Alexandrian history. Following a general trend, in the 1990s, research increasingly focused on the history of the city in Late Antiquity. Nevertheless, the theorem of the decay of ancient urban culture which gave rise to an allegedly intolerant and violent Christianity, implicitly remained salient in the majority of modern analyses. As a result, those studies draw a picture according to which the cosmopolitan intellectual center – the ancient melting-pot and erstwhile πολύπολις of the Romano-Hellenistic era – got caught up in the maelstrom of bloody inter-religious conflicts, to be finally resurrected as the ‘Christ-loving city’ (ἡ φιλόχριστος πόλις). This process has commonly been interpreted as a symbolic and functional conversion as well as the deliberate destruction of urban structures with religious meanings.

The above mentioned shortcomings are:

1. Hitherto, the underlying concept of Christianity has been underdetermined and primarily been perceived as a teleological one in the context of urban topography. Moreover, it seems to represent an essentialist and normative notion of the Christianity and, thus, prevents a consideration of possible reciprocal developments.

2. Though the construction of two dichotomous entities – ‘pagans’ vs. Christians – crusading for the urban space may be quite convenient at a literary-discursive level, they do, however, not constitute an adequate representation of the socio-historical reality.

3. Spatial competition between cult groups presumes a certain functional and symbolic equivalence in terms of sacred conceptions of space. Early Christian theologians deny the existence of Christian sacred places before the fourth century AD.

First results

In order to overcome these inconsistencies, the thesis analyzes, at first, the specific local initial conditions that structured the scope of action and the Christian perception(s) of the Alexandrian urban space in the fourth century AD. It has come to light that the development of locatable sacred spaces was a multifactorial, empire-wide process – initially, within the Christian community only – which, however, followed different regional and temporal patterns, together with all its spatial-sociological and theological consequences. The genesis of the Christian topography in Alexandria took place where, in the course of numerous intra-Christian disputes, the claims of the local Alexandrian Church clashed with those of imperial politics. The sites of those conflicts (St. Dionysius church, St. Theonas church, Caesarium) became crucial for the formation of the Alexandrian Nicene congregation’s identity. Thus, the seizure of those semantically meaningful ecclesial spaces by an anti-bishop often resulted in combative violence. So far it can be subsumed that the ‘sacred’, being the reason for the struggle for power in the urban space of Alexandria, was, at the outset, a purely ‘inner-Christian’ phenomenon, which eventually led to a semantic superimposition of the urban space.

As a second step, the relationship between group-specific identity constructions, urban subspaces (as social spheres of action) and mechanisms of local conflict management had to be reconceived. Instead of assuming fixed religious identities, one should rather take into consideration that it was hybrid forms of identity that affected every-day practices in the urban space. Hence, it can be concluded that the acts of violence, usually orchestrated by the official Church, were not solely directed at other cult groups. Likewise, they constituted a message to their own folks to avoid multivalent and, at the same time, religiously ambiguous public spaces.

This Ph.D. thesis is being written within the program Ancient Languages and Texts (ALT) of the Berlin Graduate School of Ancient Studies (BerGSAS).